Are museums still relevant in today's society?

Are museums still relevant in today's society?

2020 Asian Cultural Council grantees Ana Tamula and Sofia Santiago strongly believe that museums are an integral part of the social fabric of any country. Museums not only aid in economic development, but also serve as a repository for history and collective memory, foster national or cultural identity, and build community.

Museums archive traditions, cultures and storied pasts, but also position us for the future. “If we are unable to learn from our past,” Ana explains, “we are bound to repeat the same mistakes and therefore suffer the same outcomes.” Museums play a role in facilitating this understanding. Sofia notes, however, the efficacy of a museum is tied to its ability to connect broadly. “For a museum to remain relevant,” she explained, “it must be democratic, inclusive and responsive to the needs of the community it serves.” In this, lies the importance of museum programming as a bridge that connects audience, artwork, and artifact; history, present, and future.

In 2019, Sofia and Ana founded The Museum Collective to provide support to museum educators in the Philippines. The Museum Collective connects and collaborates with cultural workers, museum workers, educators, and artists to initiate contextualized practices and programs that are responsive to the needs of the times. Since museum studies is an emerging field in the Philippines, Ana and Sofia decided to pursue an ACC Fellowship to learn more about museum practices across the region.

Predeparture meeting with ACC Philippines Program Director Teresa S. Rances; The Museum Collective logo

“What we really love about ACC’s Fellowships is that they are not only focused on a specific field in the arts. There is really an opportunity to grow across many fields of cultural work. For our grant, we decided to embark on a project in Cambodia to study more about historiography and memorialization,” shared Sofia who has worked in museums for seven years.

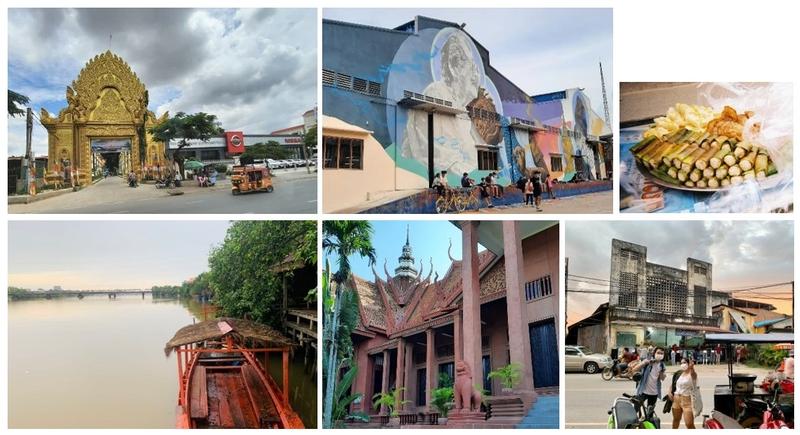

(clockwise) Phnom Penh cityscape and street art, local snacks, view from Kampot province, the National Museum of Cambodia, and façade of the old Royal Cinema

Working with Teach for Cambodia (TFC), they conceptualized and developed a teacher training program to help other TFC fellows in using museum exhibits, collections, and archives in the classroom.

Museum Education training and exchange with Teach for Cambodia fellows

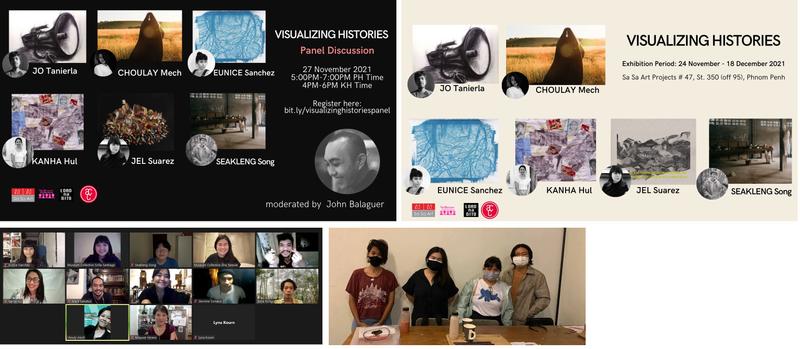

Throughout the months they stayed in Cambodia, Sofia and Ana worked with various partners, including Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center and Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. They have had ongoing collaborations through the exhibit “Visualizing Histories” at SaSa Art Projects with Cambodian and Filipino artists—Jo Tanierla, Choulay Mech, Kanha Hul, Eunice Sanchez, Jel Suarez and Seakleng Song, Load Na Dito (LonaDi)’s Mayumi Hirano, Mark Salvatus, and Gerome Soriano. The project seeks to underscore how contemporary art can effectively aid in memorializing sensitive truths in history. Each artist created a work highlighting a part of Philippine or Cambodian history that would otherwise have been forgotten or neglected.

Online and in-person interactions with artists in Cambodia

“Some focused on history from the peripheries; while others took on a more personal approach. Some focused on things that can be easily observed such as one's daily activities. By doing this, we learn that human beings are the vessels of history,” shared Ana, noting particularly the work of artist duo Choulay Mech and Jo Tanierla.

The idea is to examine history from a micro perspective.

“Oftentimes, history is examined through a macro lens. When we study wars, we often think about numbers – the dates, the number of casualties, the number of survivors. When we do this, history becomes impersonal and far removed from the present,” said Sofia.

Ana continued, “History, however, is much more than this. It is the story of humanity. It is about the triumphs and struggles of men. It is more than anything a guide for people in the present. So, by seeing how history directly affects people today, history can be used as an effective tool for teaching empathy and compassion. Museums can do this by creating programs that show history from a more micro perspective.”

Meeting Chhay Visoth, fellow grantee (ACC 2010) and current director of the National Museum of Cambodia (presently undergoing conservation and building restoration efforts)

For two months, Sofia and Ana immersed themselves in Cambodian history, culture and traditions, and experienced the cultural sensitivities and social nuances of their host country.

“We wanted to know how [individuals and communities in Cambodia] were able to effectively memorialize and remember dark histories and how they were able to inculcate the Southeast Asian context. We feel the need to adapt similar practices back home given how we treat history and historiography,” said Ana and Sofia as they noted similar themes in the Philippines and Cambodia. Both have “suffered through different atrocities due to colonization, wars, dictatorship, and the continuous struggle of people who are not really represented in narratives shown in textbooks or even in exhibitions.”

In all their exchanges, they noticed the conscious and genuine effort for inclusivity and accessibility in museums and archives across Cambodia. The programs are free and available for all, with outreach programs extending to those outside of the capital. For instance, Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center equips indigenous communities with tools to tell their own stories through documentary training programs. Meanwhile, SaSa Art Projects engages students in the curatorial process.

A visit to Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center and meeting its director Sopheap Chea

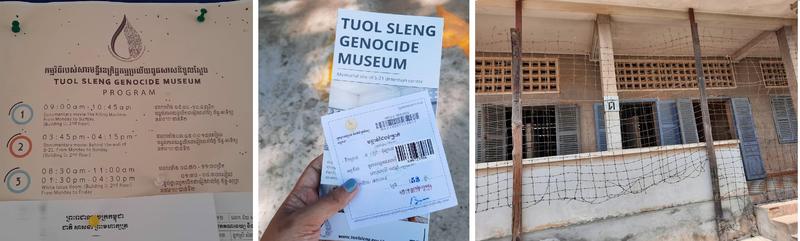

In addition to research, Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum has numerous programs for public school teachers and students to send messages of peace, reconciliation, and healing. Their staff is encouraged to take on capacity-building opportunities and fellowships through research, utilizing their archives, or participating in workshops, talks, and lectures organized by local and international organizations.

(clockwise) Ana and Sofia with Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum Director Hang Nisay and Head of Archives Pheaktra Song; Meeting and exchange with the museum’s Exhibitions and Education Team; Museum Conservator Kho Chenda explaining their textile conservation efforts to Sofia and the processes of preserving the clothes of the prisoners, guards, and other staff in the former prison facility.

Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum is the memorial site of the S-21 (Security Prison-21), interrogation and detention center of the Khmer Rouge from 1975 to 1979, and formerly the site of a public school.

Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum is the memorial site of the S-21 (Security Prison-21), interrogation and detention center of the Khmer Rouge from 1975 to 1979, and formerly the site of a public school.

“We learned how these institutions listen and engage with the communities that they serve and the people who are working inside the institutions. We learned how to be more empathetic: to listen more to individual stories and to respect how they navigate through their difficulties, as well as their victories, through the process. We will really carry that even after residency,” shared Sofia.

With this experience, Sofia and Ana have developed a stronger affinity with Southeast Asia. “I have always felt strongly about being Filipino; however, I had never thought of my connection to the region,” Ana explained, “This experience changed that completely. One of the reasons for this may be because of our shared experience as a colonized country. We often talk about the different remnants and visible manifestations of these past cultures into modern-day society.” For the duration of their residency, Sofia and Ana will continue to engage in conversations and collaborations to widen their perspectives regarding Southeast Asia, memorialization, museums, trauma, historiography, contemporary art, and humanity.

Bou Meng and Chum Mey are the last two remaining adult survivors of S-21 living today. They share their stories through the museum's testimonial program, conversing with visitors. Chum Mey was a mechanic, who survived by performing repairs for typewriters used by interrogators, while artist Bou Meng was made to create sculptures and paintings for Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot.

ACC New York

ACC New York